Socio-cultural Practices of the Mishmi tribe around Kamlang Tiger Reserve

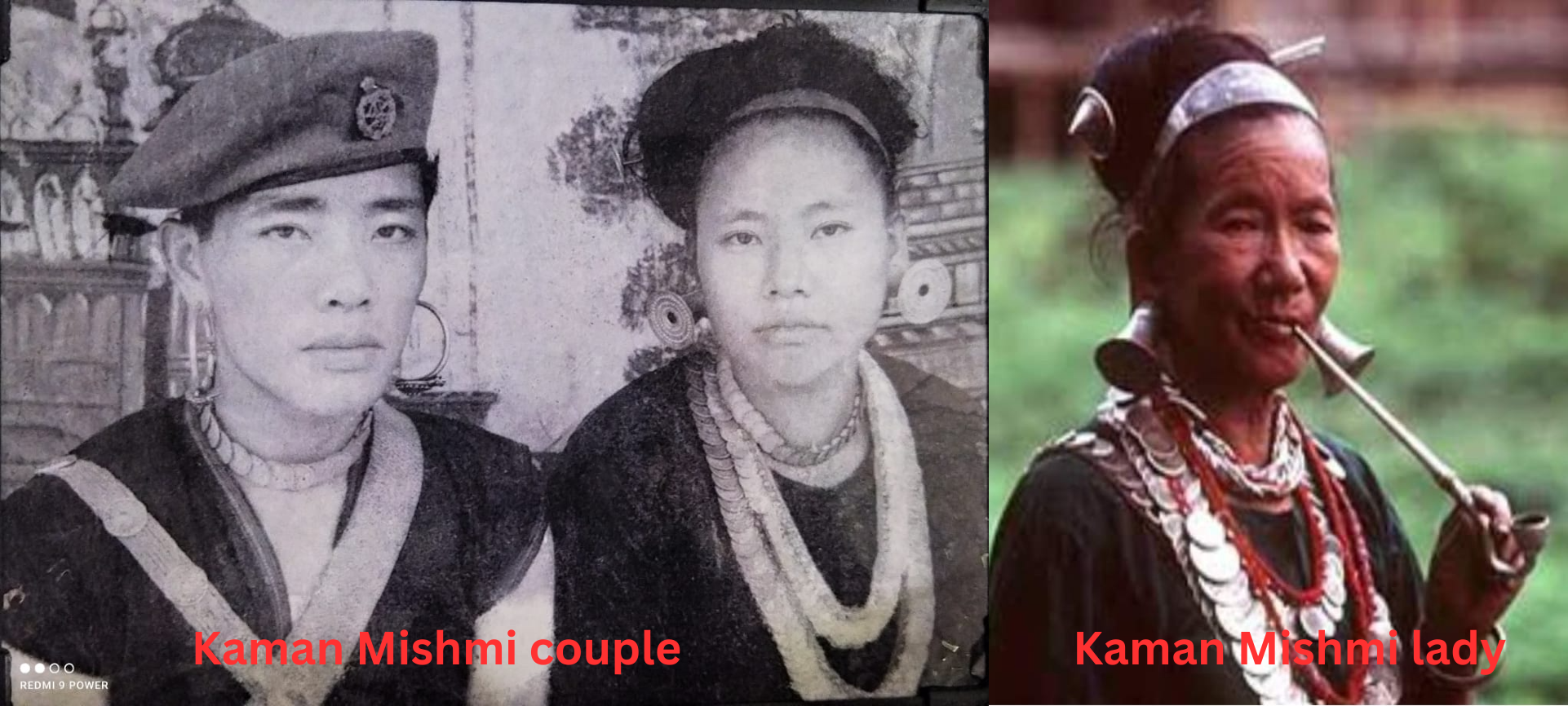

The indigenous population that lives around Kamlang tiger reserve belong to the ethnic group, Mishmis comprising two tribes which are the Miju Mishmi or Kaman mishmi and Digaru Mishmi or Taraon mishmi. They are animists in their religious beliefs and worship various elements of nature. Their ancestral homes are often found perched in hills, much beyond the reach of other people. Traditionally they have practiced shifting agriculture and cultivated corn and buckwheat. They are excellent weavers and make exquisite handicrafts from bamboo and cane.

Miju Mishmi has their own panchayat system called Kabai and the Sarpanch is called Kabai Mai. They live in long rail homes with 10-15 compartments in which they share space. It's divided into various sections. The first room is for visitors and religious purposes, the second is for the house guardians, the third is for the other family members, and the fourth is for the children.

Mishmi believes in the presence of several spirits (kheenu), in farms, houses, forests and mountains. These spirits help in providing farm products, wild animals, safety, health and wealth to the Mishmi. To achieve this, people follow a code of conduct and behavior in order to receive blessings from these spirits and success in farming and hunting. If people fail to satisfy these spirits, harvests may fail and hunts can be unsuccessful.

The narrative of the Mishmi reflects a place-based conservation emphasizing the role of local communities and bottom-up local decision-making processes. The Mishmi claim that their culture protects tigers and it is only because of their culture that tigers still exist in the forests.

According to the Mishmi mythology, Mishmi and tigers were born to the same mother and were siblings (tiger, the elder brother and human, the younger brother). The younger brother shot a deer and handed it over to the older brother to collect firewood. He was scared to find his sibling eating the meat raw when he returned home. 'My younger brother is a tiger,' he said to his mother. If he can eat raw flesh, I'm sure he'll eat me one day as well.' The mother devised a scheme to pit the two brothers against one another. The first person to cross the river and reach the other side would be killed. The tiger chose to swim over the river, whereas the Mishmi chose to cross across the bridge. The mother threw an ant nest on the tiger's body as he emerged from the water, preventing him from winning. Returning to the river, the tiger scratched his body against a rock. Meanwhile, the Mishmi had reached and ascended the bank, shooting the tiger with an arrow. The tiger died as a result, and its body flowed down the river, washed away to a distant location. A bird saw the tiger's bones spread around the riverbank several years later. The bones were dazzling white and gleamed in the sunlight. The bird sat on the eggs, mistaking them for eggs. The tiger evolved from these bones, while the leopard, leopard cat, clouded leopard, and civet cat evolved from smaller bones. This is the story of a tiger's rebirth. This narrative also explains why the Mishmi avoid killing tigers.The Mishmis also regard Hoolock gibbons (Hylobates hoolock, Amepon in the local language) as sacred, in addition to Tigers. Gibbons, like tigers, are protected by religious authorities1 . When seeking to incorporate Mishmi taboos, cultures, and beliefs on natural forest deities into long-term conservation frameworks, the entire processes underpinning these taboos, cultures, and beliefs on natural forest deities matter just as much as the outcomes2 . Certain prospects and awareness programmes along with the Mishmi communities are already helping in conservation of several big faunal diversity and its ecosystem.

Their subsequent position as a Special Protection Task Force in collaboration with the Forest department raises the emphasis of protection of the region's whole biodiversity and its long-term viability for future generations. This is by far the most important contribution to the development of culture-based conservation methods, and it will arguably be stressed.